Quick preface: this post is about a NixOS specific issue and thus expects some base level Nix experience. Hopefully soon when I have more time I’ll write more about how Nix works, why to use it, its tradeoffs, etc. That’s for another time though for now.

Python Venvs

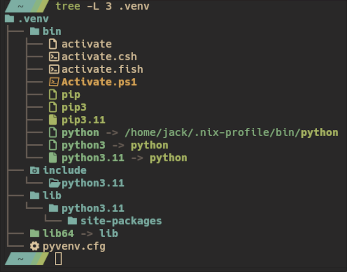

Python virtual environments (venvs) are the official solution for managing python dependency hell and version conflict. They’re super nice; each project gets its own venv which houses all the project’s dependencies/libraries separately from everything else on the system in a simple and familiar layout:

Creating one is as simple as python -m venv .venv using your system-installed

python, which is then set to be the python interpreter for that venv via a

symlink (just use a different python3.x binary during setup to set a different

python version for that venv).

To “enter” the venv, run source .venv/bin/active (or whatever the equivalent

is for your inferior OS). Now pip as seen in the directory tree is added to

your path, and you can pip install xyz just as if you were installing

globally, but it only affects the local venv!

Python in NixOS

NixOS has it’s own special way to manage python installations. Nixpkgs, the Nix package collection, has over 8 thousand python libraries packaged as first class derivations, which are composable with any given python interpreter to create fully isolated, infinitely granular, unbreakable and immutable python installations. It’s extremely powerful (far more than regular python venvs are), however it requires a complete paradigm shift, which isn’t beneficial whatsoever for those not using Nix. So, especially when working with teams, it’s sometimes just not worth the extra effort.

Thankfully venvs work just fine with Nix’s python binaries. Just put any python version into your PATH and use the same command as above. There’s a catch though, and it has to do with compiled python libraries.

Compiled Python Libraries

Many if not most python libraries (eg. numpy, polars, pandas) are written in more efficient compiled programming languages and exposed as python wrappers around the more efficient code. This requires compiling native executables (or shared libaries) for the target machine and having python load them into the runtime correctly. However, these compiled libraries are often dynamically linked, requiring other dynamic libraries (libstdc++.so.6 for example) to be present on the system to run.

On most linux/unix systems this is all well and good as the libraries are

present in /usr/local/lib/ and the dynamic library loader

(/lib/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2) which python is linked against knows how to find

them there. However, on NixOS, those libraries don’t exist there, but rather in

the Nix store (/nix/store/…)! And since we don’t control the compilation

process of python libraries from pypi, we aren’t able to patchelf them

automatically to reference the nix store library paths instead.

Of course since python is so popular there is a dedicated wiki.nixos.org page for this. There’s few solutions listed:

- The first one is a tool that runs

patchelfon all the compiled libraries in your venv, but it requires setting up the venv a little differently and a manual run on every package update, which feels too clumsly - The second one recommends using

buildFHSEnv, which basically puts your shell in an environment that emulates the regular FHS paths like /lib. I’ve used this a lot before and it works well, but still requires manual setup work for each new python project, which I’d like to avoid. - The last suggestion is to use a tool called

nix-ld, which is what I’ll be going with!

Nix-ld

Nix-ld’s intended purpose is indeed to make unpatched dynamic executables run transparently on NixOS, which is exactly what we’re looking for! To accomplish this, it inserts a set of user-defined shared libraries (usually just the minimum necessary) into a path specified under $NIX_LD_LIBRARY_PATH, and adds a wrapper dynamic library loader at the default FHS path which simply adds the aforementioned shared library path to $LD_LIBRARY_PATH before jumpstarting the regular dynamic library loader. That’s a lot of jumble to basically say, it gives all unpatched dynamic executables access to a set of user-defined shared libraries using environment variables.

There’s one problem with this though, which is mentioned in nix-ld’s readme: This breaks subtly when using interpreters from nixpkgs that load the unpatched dynamically compiled libraries; which is exactly our case with Nixpkgs python. This is because in order for the nix-ld shared library path to be used by the interpreter when loading the compiled libary, the interpreter needs to have been started using the wrapper dynamical library loader created by nix-ld, as it does the task of inserting the path into $LD_LIBRARY_PATH of the child process. We can see that it’s still failing, even after installing nix-ld:

python main.py

> ImportError: libstdc++.so.6: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory

The Full Solution

So, since Nixpkgs python isn’t started with the wrapper dynamic library loader (because it’s properly patched!), we have to do the job of telling it to use the nix-ld shared library path ourselves. We can just do:

LD_LIBRARY_PATH=$NIX_LD_LIBRARY_PATH python main.py

This is already enough to get our python interpreter to properly load dynamic compiled python libraries. But this requires an ugly environment variable manipulation every time you want to call python or pip! Unacceptable. Instead, I prefer to wrap all of the python binaries installed on my system to do this for me, so that I can manipulate venvs without ever having to think about it. This is the generalized solution I came up with to do just that:

home.packages =

let

# Some dynamic executables are unpatched but are loaded by patched nixpkgs

# executables, and therefore never pick up NIX_LD_LIBRARY_PATH. For

# example, interpreters that use dynamically linked libraries, like python3

# libraries run by nixpkgs' python. This wraps the interpreter for ease of

# use with those executables. WARNING: Using LD_LIBRARY_PATH like this can

# override some of the program's dylib links in the nix store; this should

# be generally ok though

makeNixLDWrapper = program: (pkgs.runCommand "${program.pname}-nix-ld-wrapped" { } ''

mkdir -p $out/bin

for file in ${program}/bin/*; do

new_file=$out/bin/$(basename $file)

echo "#! ${pkgs.bash}/bin/bash -e" >> $new_file

echo 'export LD_LIBRARY_PATH="$LD_LIBRARY_PATH:$NIX_LD_LIBRARY_PATH"' >> $new_file

echo 'exec -a "$0" '$file' "$@"' >> $new_file

chmod +x $new_file

done

'');

in

with pkgs; [ ... (makeNixLDWrapper python3) ... ]

Taking a look at the embedded bash script more closely, with our python example (All nix store paths are automatically substituted in during the build process):

mkdir -p /nix/store/xgb<...>xsc-python3-nix-ld-wrapped/bin

# the python derivation has 14 binaries and/or aliases! Let's wrap each one

for file in /nix/store/3wb<...>jir-python3-3.11.9/bin/*; do

new_file=$out/bin/$(basename $file)

echo "#! /nix/store/1xh<...>qns-bash-5.2p32/bin/bash -e" >> $new_file

# !! Insert user-defined shared library path into child process

echo 'export LD_LIBRARY_PATH="$LD_LIBRARY_PATH:$NIX_LD_LIBRARY_PATH"' >> $new_file

# !! Call the unwrapped binary, but set its argv[0] to this wrapper script

echo 'exec -a "$0" '$file' "$@"' >> $new_file

chmod +x $new_file

done

I found that it’s important to set argv[0] of the child process (regular unwrapped python in our case) to be the path to its wrapper script instead of the regular binary (see the exec -a flag). This is because if you don’t, creating new venv’s will symlink the unwrapped python interpreter into the venv, which will replace the wrapped one as soon as you enter rendering the wrapper useless.

(I also did try using bash heredocs instead of the separate echo’s, but kept getting mysterious syntax/formatting errors. Bash is so cursed lmao)

That’s all, hope you enjoyed or learned something :P